New international shipping decarbonisation targets agreed

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has agreed its revised GHG Strategy, providing the shipping industry with some of the clarity it needs to plan decarbonisation strategies

Climate action in the near-term remains urgent

It remains important to recall why we must act to mitigate climate change. The IPCC’s 6th assessment report (synthesis report) spells it out very clearly:

“Climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health (…). There is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all (…) The choices and actions implemented in this decade will have impacts now and for thousands of years”

What has been agreed at the IMO?

The IPCC’s work was the backdrop that many IMO Member States (as well as observer intergovernmental and non-governmental organisations) negotiated hard for ambitious targets over the last week of June and the first week of July at the IMO’s headquarters in London.

Several delegations participating in the IMO meetings highlighted the study led by Ricardo, titled 'on the readiness and availability of low- and zero-carbon ship technology and marine fuels'. This research paper was among the papers submitted for this IMO meeting's agenda.

This study, commissioned by the IMO and carried out in collaboration with DNV, identified that alternative fuels and technologies have reached a level of technological and commercial readiness that enables the decarbonization of the maritime industry. It emphasized the importance of policymakers providing a clear and early signal of demand to facilitate progress.

These arguments were pivotal for multiple delegations in advocating for a more ambitious pathway to achieve their goals.

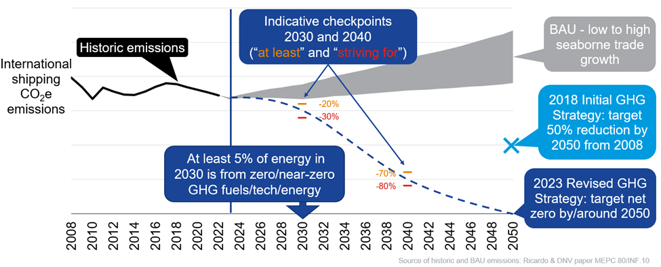

Prior to this fortnight, the sector had a 2018-agreed Initial GHG Strategy of reducing emissions by just 50% by 2050 compared to 2008 levels. Given the developments in the last five years, including recognition that under the Paris Agreement additional action is needed beyond business as usual to aim for limiting global average temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, that 50% reduction target was no longer considered ambitious enough.

It has also been widely recognised (including in our study cited above) that the agreed global policies and measures tackling GHG emissions from the maritime sector remain insufficient to achieve event this Initial Strategy.

|

What has emerged as the outcome of the negotiations this fortnight is the step change needed to kick-start a more significant decarbonisation of the sector. The Revised Strategy (Figure 1) includes: |

Figure 1 - Ambition level of the revised IMO GHG Strategy, showing possible ‘s-curve’ pathway from today’s emission levels through the 2030 and 2040 checkpoints to zero in 2050.

The IMO’s work on life cycle emissions also made progress at the talks. The meeting finalised and adopted the first version of guidelines on life cycle GHG intensity of marine fuels, as well as acknowledged there was a need to continue the development of the guidelines, as several potential default values for GHG intensity of fuels remain to be agreed.

When will we have the full clarity on the policy measures to achieve this transition?

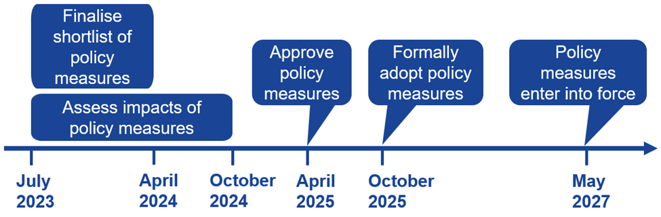

The IMO talks that have just concluded with revised targets did not aim to also agree the policy measures that will enable the sector to transition to the new targets, that discussion will continue into the next planned committee meetings. The timeline of agreeing the policies is now more substantially known (Figure 2), with approval of the policy measures expected to be in 2025, and then coming into force in 2027.

Figure 2 – Timetable expected for shortlisting, assessing and adopting policy measures

The ‘mid-term’ policy measures to achieve this transition with more significant emission cuts look likely to be in the form of a ‘technical’ measure combined with an ‘economic’ measure.

The technical measure is likely to be some form of a goal-based fuel standard, regulating the phased reduction of the GHG intensity of fuels used in ships. This ratchetting downwards of a required standard for fuel GHG intensity may well have some sort of flexibility mechanism to incentivise first movers and enable them to sell credits to those behind the curve. The stringency of the regulation would be set at the level needed in order to achieve the ambition of the GHG Strategy.

This will, together with the specifications from the life cycle guidelines, therefore, imply which fuels will be needed by when (or alternatively, which fuels would no longer be possible to use by when).

There is less certainty about what the economic measure will be, and we should encourage further information exchange at international level about possible maritime GHG emissions pricing mechanisms. Such economic measures would provide the means to generate revenue streams for potential disbursement to those which will be most negatively impacted economically by the technical measure.

For example, remote small island developing states, whose imports and exports incur higher maritime transport costs, and who may be hit hardest economically by the shift to more expensive alternative fuels. To reinforce the mid-term measures tackling switches to alternative fuels, we also expect a need for tightening the existing ‘short-term’ policy measures to improve energy efficiency of ships.

What can the industry expect?

- A shift away from conventional fuels. The push for triggering a tipping point by switching to at least 5% zero or near-zero GHG fuels by 2030 will provide showcasing/leadership opportunities for the industry through demonstration projects e.g. as part of green corridors. The legislative drivers for longer term will provide the clarity for industry with known required reductions in energy intensity by year. This will imply by conventional fuels will be effectively require switching out. This is to an extent already within the EU’s FuelEU Maritime initiative (requiring a 31% reduction by 2035, with targets for every 5-year period), which will get superseded globally by the IMO’s ‘technical’ mid-term measure. Industry players choosing to act before they are pushed will gain a financial benefit and lower their risk of stranded assets.

- Pressures on the supply chain. We expect to see pressure on shipyards (many of which already have large orderbooks), engine manufacturers and the fuel supply industry to deliver on the demands of this revised strategy. However, this strategy also provides these stakeholders and their financiers the clarity needed to make these long-expected investments to deliver the energy transition.

- A range of energy sources being used. Transoceanic voyages may well be constrained by the more energy intense offerings of (green) methanol, (green) ammonia, and synthetic or bio-based drop-in fuels. Whereas shortsea shipping and port/harbour craft could make greater use of hydrogen and battery-electric propulsion.

- The need to be more efficient with using energy to minimise demand on (alternative) fuels. The higher costs of alternative fuels in themselves will naturally create a demand driver for this, in a resource-constrained world. Additional legislative push through tightening of energy efficiency standards would support this, including additional propulsive power from e.g. wind. (Decarbonised) shore power will also be important to eliminate at berth emissions in ports.

- More refuelling locations. There will likely be a shift in the bunkering practices of vessels – a diversification to a wider number of refuelling locations due to wider number of energy sources and the lower energy densities of these fuels. New bunkering locations may appear in countries that have good access to low-cost renewables, for example North Africa, rather than the traditional bunker locations. This presents economic opportunities for those regions, as we’ve exemplified in previous studies with case studies on Morocco, Chile, Mexico, South Africa and Indonesia.