How race circuits can improve their carbon footprint

31 Mar 2025

When you are watching your favourite drivers battle for the lead, the environmental impact of racing may not be at the front of mind. But in today’s world, every organisation has a responsibility to move towards a net zero future. Of course, the very nature of motorsport makes this a particular challenge, as it essentially involves thousands of people travelling to racetracks all over the world to watch cars race around circuits.

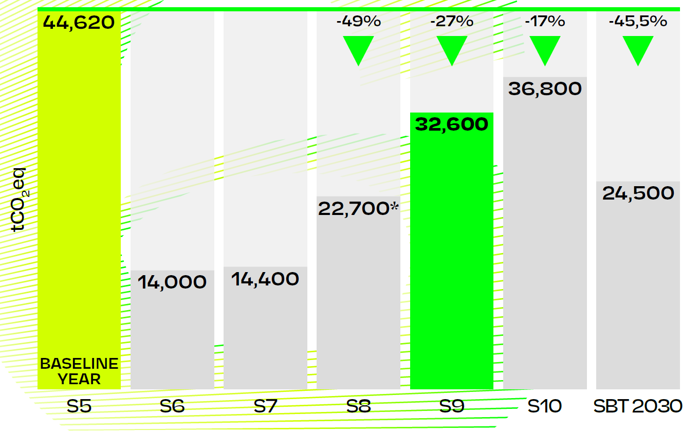

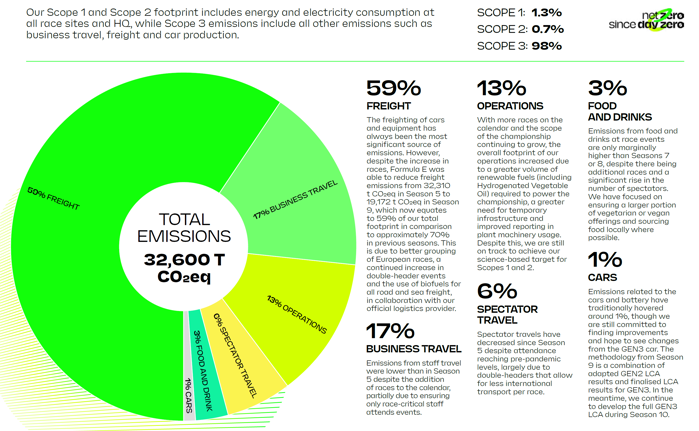

In fact, Formula 1 estimated that its total carbon footprint for the 2022 season, including scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, was 223,031 tCO2e[1]. That’s roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of 48,000 gasoline powered cars[2]. For comparison, the carbon footprint of Formula E season 9 was 32,600 tCO2e and the 24 hours of Le Mans is around 36,887 tCO2e[3].

So how is this carbon footprint measured and what can circuits do to reduce their environmental impact?

The science behind carbon footprints

A carbon footprint estimates the total volume of greenhouse gases emitted directly and indirectly by an organisation, action or product. These gases can include carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and fluorinated gases, although carbon footprints are typically expressed in terms of metric tons of CO2 equivalency (tCO2e). This allows easier comparisons between the environmental impact of different industries.

Carbon footprints are made up of scope 1, scope 2 and scope 3 emissions. Scope 1 are direct emissions from sources owned or controlled by an individual or organization such as the burning of fuel on site to heat buildings and run equipment as well as the fuel burned in company owned vehicles. Scope 2 are indirect emissions from purchased energy such as the generation of off-site electricity. Whereas Scope 3 emissions are all other indirect emissions related to a business and include travel, purchased goods and services, production, distribution and disposal.

Carbon footprint contributors

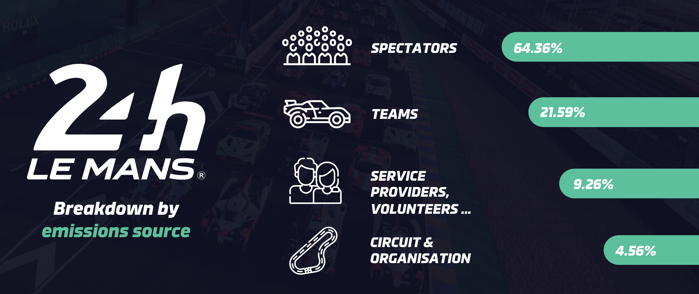

In the racing world, the emissions resulting from the racecars themselves out on track account for a very small percentage of a championship’s carbon footprint – less than 1% in the case of Formula 1. The majority of emissions result from the logistics of transporting all the necessary freight across the globe. This combined with spectator travel makes Scope 3 the largest contributor to a series’ carbon footprint. In fact, Scope 3 makes up 98% of Formula E’s emissions [4], while spectator travel accounts for 64% of the emissions of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and nearly half of Formula 1’s carbon footprint is down to logistics.

‘When it comes to the carbon footprints of race circuits, it’s actually quite interesting,’ highlights Rachel Mason-Salkeld, Principal Consultant - Sustainability, Energy & Carbon Management at Ricardo. ‘Most of the year they are relatively quiet, but then on those weekends where they host major series, they become mini cities as they accommodate all the additional equipment, food, entertainment and facilities on site. So those few weekends make up the majority of their environmental impact for the year, both in terms of goods and services procured, the power use and also the amount of waste generated, whereas their core corporate emissions are much smaller.’

During those major race weekends, it is the travel of the spectators to and from the event that are the biggest contributor to a circuit’s emissions. ‘This is compounded by the fact that historically most circuits are in remote locations because they were originally based on airfields,’ comments Stuart Cooper, Market Head for Motorsport at Ricardo. ‘So for most tracks, the easiest mode of transport is by car, which fans often prefer travelling in to a motorsport event anyways.’

Initiatives to reduce emissions

To help reduce the environmental impact of spectators, there are several tactics circuits can use. They can temporarily increase public transport connections, providing park and ride buses for example, to shift more spectators to lower carbon travel. Circuits can also install more electric vehicle chargers so that people have the option to travel in zero emission vehicles.

‘One of the advantages of the remote locations of tracks is they have the space to generate their own electricity on site,’ says Mason-Salkeld. ‘Another key source of emissions is the extra power necessary during race weekends which is often solved with generators running on red diesel. However, Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO) can be used instead which has much lower emissions.’

‘Many tracks have also installed rooftop solar panels to help satisfy the increased power demand,’ adds Mason-Salkeld. ‘But there’s nothing stopping venues from getting more creative and generating renewable energy themselves, particularly in rural locations.’

Where renewable power is not an option, there are alternative power sources that are more environmentally friendly than generators. ‘When you walk down the pitlane of races like the Daytona 24 hours, there are at least three diesel generators per garage, so there’s a real opportunity to take advantage of auxiliary energy storage units,’ says Cooper. ‘Ricardo has a broad scope of technologies for auxiliary power including chemical storage such as hydrogen fuel cell, and electrochemical storage such as batteries.’

‘Although these units are on the back of a truck, which has to travel, and therefore contributes to emissions, everybody could plug into that power source, which would offset the number of generators being used in the paddock.’

Decarbonising a race event is a monumental task and requires collaboration from the circuit, teams and spectators, but also all the hundreds of suppliers that come onto site as well. ‘Circuits need to engage with their suppliers and make them aware that they also have a part to play in the wider decarbonisation strategy,’ explains Mason-Salkeld. ‘It’s very difficult to quantify the environmental impact of this army of smaller organisations but working with them to see if they can use recycled food containers or source produce more locally for example, can actually have a large impact on a circuits overall carbon footprint.’

Driving change

One of the best ways to accelerate this movement to reduce emissions is to make it a contractual obligation. With major series now regularly reporting on their carbon footprint, it won’t be long before event organisers require circuits to have their own decarbonisation strategy in place - which could be the difference between winning and losing the opportunity to host major race events.

‘Any business is always looking for a return on investment and being green, at the moment, does not give the biggest return financially,’ comments Cooper. ‘So, there has to be a mindset shift and that will be triggered when championships mandate decarbonisation strategies of its venues. It also needs to work from the bottom up, where clients request venues to lower their carbon emissions. It can become a selling point to run zero carbon events, particularly within the hospitality sector. Motorsport is such a high visibility area, that it can really lead the charge from the front and be an example of change that then filters down into wider society.’

As well as developing hardware, such as auxiliary power units, Ricardo also delivers holistic end to end support for race circuits, helping them calculate, understand and reduce their environmental impact.

‘Our experts start with measuring the carbon footprint,’ explains Mason-Salkeld. ‘This is particularly challenging as racing doesn’t fit within conventional GHG protocols and tools, so you need motorsport experts to accurately calculate a race circuit’s emissions. We then have the capability to develop decarbonisation strategies and implement those measures with our various power, heat, transport, waste and water teams.’

‘The amount of change required to achieve net zero means that everyone is going to have to work together, there can be no abdication of responsibility,’ concludes Mason-Salkeld. ‘We need venues to run zero emissions events and provide the resources that allow teams and fans to change their habits. We also need suppliers and teams to rethink the amount of equipment they bring on site and spectators to embrace low carbon travel. Only then can we significantly reduce the environmental impact of race weekends.’

References

[1] 2023 Formula 1 Impact Report [Online]. Formula 1.

[2] Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle [Online]. EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency.

[3] Race to 2030 [Online]. 24 Hours of Le Mans & ACO.

[4] Racing for Better Futures Season 9 Sustainability Report [Online]. Formula E.

Subscribe or ask us a question

Subscribe for updates or get in touch with our experts about this article or about our motorsport services, or email us at info@ricardo.com

Follow Ricardo Motorsport and High Performance Vehicle for regular updates

Follow Ricardo Motorsport and High Performance Vehicle for regular updates