The opportunities and challenges of motorsport’s shift to standardisation

22 Jul 2024

The fierce competition of racing has always made motorsport an ideal platform for innovating technology. This not only enhances the performance of the cars on track, but also transfers to other industries such as automotive, aerospace, defence and medical. For example, the paddle shift gearboxes raced in F1 in the late 1980s have featured in roadcars for decades, while KERS regenerative braking reduces emissions of today’s buses and F1-style data monitoring systems are utilised by air traffic controllers and hospitals [1].

Standardising such a fruitful development laboratory seems counterintuitive, yet more parts, systems and championships are standardised than ever before. How is this shift changing the face of motorsport and what does this mean for suppliers?

What is standardisation?

Standardisation is where the regulations define that only components that meet a particular specification can be used. These components range from small nuts and bolts to entire chassis or powertrain assemblies.

‘Standardisation doesn’t necessarily mean that everyone is using exactly the same part,’ explains Stuart Cooper, Market Head of Motorsport for Ricardo. ‘It just means that the part everyone is using is of the same specification. Standardisation has been around in motorsport, in some form, from the very beginning because it’s key to orchestrating competitive racing.’

‘However, in the past it was more open, so several manufacturers could supply a particular standardised component,’ continues Cooper. ‘Whereas now we are seeing championships standardising more parts and larger assemblies, but also only choosing one supplier for a specific part.’

Why is standardisation increasing in motorsport?

There are now so many standard parts in Formula 1, the regulations specify a Standard Supply Components (SSC) list. This includes parts which have been spec for years such as the tyres, fuel flow meter and ECU, as well as more recent additions like wheel covers and wheel rims [2].

The likes of Formula E and LMDh take this a step further with standardised chassis and powertrain assemblies. Formula E uses a spec battery and front powertrain kit, while LMDh has common motors, gearbox, batteries and control electronics. The main reason behind this spread of standardisation across motorsport is to reduce costs and therefore lower the barrier to entry for teams. By providing a standard platform, teams no longer have to plunge resources into developing major components to be competitive, making motorsport a more feasible business proposition.

‘It also helps make the performance between teams more comparable, which can result in closer and more exciting racing,’ highlights Vlastislav Frič, Principal Engineer at Ricardo. ‘The racing then becomes more about the skill of the driver or the way the team optimises the car, rather than who spends the most money.’

However, can restricting the opportunity for development stifle innovation – one of the cornerstones of motorsport’s existence? ‘I don’t believe that standardisation kills technology, I think it focuses teams on developing areas that are more important to wider industry such as the powertrain,’ comments Cooper.

‘Standardisation is not a negative, the performance gain or loss of a spec component is the same for everybody,’ continues Cooper. ‘When I started working in motorsport, we would take 20 engines to a Formula 1 race. This is simply not possible now from both a cost, but more importantly, sustainability point of view.’

What does the future hold for motorsport transmissions?

What motorsport standardisation means for suppliers

Standardising the spec of components brings several benefits to suppliers. Instead of modifying parts between races, manufacturers supply the same design for the entire season, extending the lifecycle of components. This leads to regular and repeating business that is much easier for a manufacturing facility to manage.

However, in some cases to guarantee the fairness, safety and cost of motorsport, the governing bodies select either one or a handful of manufacturers to supply a spec component. This restricts business to only a few companies, who have to think differently about their approach and business model.

Regardless of whether it is for a spec series or not, interested companies go through a tender process. This is where the governing body issues a dossier detailing the terms of the tender along with the specification of the part. Manufacturers are then invited to submit a bid and the regulators decide who will win the supply for the next term.

Find out more about the FIA tendering process

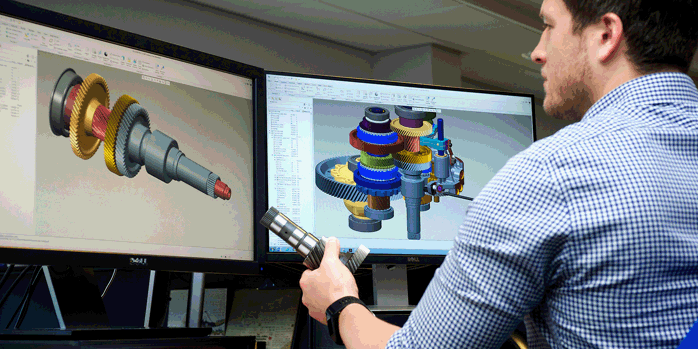

‘This tender process requires a different approach to design and development,’ explains Frič. ‘As the design is fixed for several years, there is no opportunity to improve the part, unless there are reliability concerns. So, you have to invest in all the R&D work upfront, within the bandwidth the tender allows, to deliver the best product you can at the point of entry.’

‘There is also more emphasis on reliability, because you need to ensure that your part will last for the entire term of the contract, which can often be several seasons,’ continues Frič. ‘This means you not only need to conduct more rigorous testing, but you also need to front load this testing phase as well.’

The Ricardo approach to spec supply

Successfully securing a tender contract can be extremely challenging, particularly if it is for the sole supply of a component. Tenders typically specify the performance requirements of a part, but often don’t detail the space the part should be packaged into. Consequently, manufacturers have to approximate much of their design, whilst keeping an eye on costs and ensuring that their part outperforms the bids of other suppliers.

‘It’s the classic chicken and egg scenario,’ says Frič. ‘The tender specifies performance characteristics, but to achieve those you need to understand the boundary conditions of the volume you have to work in. At Ricardo, we have a lot of experience in this area.’

The engineers at Ricardo start with the somewhat loose regulations of the tender, and then gather as much information as they can from teams to better understand the concepts that work best. They then iterate through various designs and try to come up with the best compromise between the terms of the tender, performance required and cost.

‘Ricardo’s biggest strength is the breadth of knowledge and experience we have gained from working across a broad range of industries,’ highlights Cooper. ‘The motorsport sector knows us best as transmission specialists, but we are also actively working on technologies such as hydrogen fuel cells, hydrogen ICE, battery, and electric drive unit. We are a technology partner to teams and championships, not just a supplier.’

References

[1] S.K., 2019. How F1 Technology has supercharged the world [Online]. Formula 1.

[2] 2023. 2024 Formula 1 Technical regulations [Online]. FIA

Subscribe or ask us a question

Subscribe for updates or get in touch with our experts about this article or about our motorsport services

Can't see this form? Email us here

Follow Ricardo Motorsport and High Performance Vehicle for regular updates

Follow Ricardo Motorsport and High Performance Vehicle for regular updates